Written by Yali Banton-Heath, Campaigns Communications Coordinator

To celebrate this year’s International Day of Co-operatives, the Landworkers’ Alliance are choosing to spotlight the burgeoning radical co-operative movement in Rojava, North East Syria. In light of this year’s narrative – ‘Rebuild Better Together’ – we wanted to highlight the ways in which agricultural co-operatives in Rojava offer a working example of how a communal economy based on women’s liberation, ecology and radical democracy can pave the way for a more just and resilient food system.

We spoke with two activists who are involved in the Kurdish freedom movement – Natalia Szarek from the LWA, and Jo Taylor, a coordinator at Cooperation in Mesopotamia – to learn more about the ecological and social significance of the co-operative economy in Rojava.

Where is Rojava?

Rojava is the name given to the territory of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). Historically part of Kurdistan, the region now lies within the national borders of Syria but since 2012 has been developing as a system of stateless self-governance which now comes under the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. Rojava has become a beacon of inspiration for radical social movements worldwide as a working grassroots example of a more socially and ecologically just society.

“It’s easy to establish a co-operative in Rojava”

Co-operatives form a significant part of the economy in Rojava, with the co-operative model forming the backbone of variety of different enterprises; from gardens and restaurants, to hairdressers, tailors and bakeries. As North and East Syria is a region renowned for being the ‘bread basket of the world’, the majority of the co-operatives in Rojava are agricultural co-operatives, set up on formerly ‘public’ arable land that used to belong to the Syrian state. Since 2012, this land has been allocated to local communes by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), the system of democratic governance that was set up as a result of the Rojava Revolution.

“It’s easy to establish a co-operative in Rojava” Jo tells me, “The Administration and Kurdish women’s movement are always offering support to communities who want to set them up.” Communities seeking to start their own co-operatives require barely any prior financial resources, as the AANES economics committees lend them the necessary tools and machinery for them to get off the ground, and even provide them with the seeds to grow their first crops.

The administrative backing for these local co-operatives comes from a staunch belief in a fully democratic confederalist system, and co-operatives are seen as being a key pillar in the building of Rojava’s democratic communal economy. “The idea is for the entire population of Rojava to be fully democratic” Jo explains, “so that everyone can take part in decision-making and govern themselves in an interconnected way.”

What is a co-operative?

A co-operative is different to a private enterprise in that it is democratically owned by its workers. Worker co-operatives are people-centred and share profits fairly among their worker members.

Co-operatives are led by the Co-operative Contract which ensures they conserve nature, prevent contamination of land, air and water, and use less chemicals. “One of the things that really struck me from my time in Rojava” says Natalia “was how the question of ecology was seen as a really fundamental framework for the whole political paradigm.”

From their very inception, co-operatives in Rojava are ingrained with robust ecological, democratic, and socially just principles.

“There is an urgent need for self-sufficiency”

Despite the number of co-operatives that have been established since 2012, Rojava still relies on importing basic food goods from other countries, including necessities like fresh fruit and vegetables. “But there is an economic embargo from Turkey,” Jo points out, and although some goods are still imported from elsewhere, this trade can be unreliable and often insubstantial in meeting nutritional needs.

For example, after spending a lot of time on the Semalka border crossing between Kurdish Iraq and Rojava (which is controlled on the Iraq side by the Turkish-allied KDP party of Iraq’s Kurdish Regional Government), Jo describes how she’d only see certain goods be allowed through: “Some livestock like goats and cows occasionally pass through, but you also see a lot of low-quality foodstuffs like chocolates and sweets” she says, “Getting nutritious food is hard, and this is why there is an urgent need for self-sufficiency in Rojava.”

In order to satisfy this need, agricultural co-operatives are encouraged by the Administration to grow as much fruit and vegetables as they can, and to only grow enough grain to meet their own personal needs, in an attempt to shift away from the grain mono-culture which was the priority of the old Syrian regime.

Production is therefore grounded first and foremost in meeting the needs of the local populations, and only if there is a surplus production will food be sold on local markets. But by selling at local markets at affordable prices, and keeping produce within the local economy, co-operatives are gradually beginning to ease the reliance on imported food. A focus on food production for people, rather than profit, has allowed communes in Rojava to build resilience from within.

Jinwar Women’s Village

“Building an alternative economy can bring people together”

Because co-operatives in Rojava are so deeply rooted in the local communes they provide for, they present an opportunity for the strengthening of shared experience and wellbeing. “Co-ops are trying to make more of a closed loop” says Jo, “so that everyone benefits; especially the women’s co-ops in decreasing their dependence on men.”

An inspiring example of this is the village of Jinwar, a women’s village in the Jazira region of North East Syria. The communal economy of the village is based upon keeping small herds of animals, a fruit orchard, and a few field-scale crops of lentils, chickpeas and wheat, as well as some local traditional crop varieties, too. “Only women and children live here” says Natalia, “and the village offers not just a refuge for single mothers, survivors of domestic abuse, and women who have been through divorce but a place from which to build up an anti-capitalist and anti-patriarchal economy.”

Communal villages such as Jinwar offer a space for refuge, and for collective healing and wellbeing. But they can also offer a space for social cohesion, inclusion and diversity:

“I also spent some time at a tree nursery co-operative” Natalia goes on, “a co-operative which was jointly run by some Kurdish and Arabic local residents. It represents the coming together of different ethnicities that traditionally political forces had tried to lever apart, and shows that building an alternative economy is also something that can bring people together.”

“This is something that we can learn from in our own movements here in the UK” she adds, “to not see questions of race, gender and sexuality as somehow separate to the work we do, but to treat them as intrinsic to our work.”

“Water that flows continuously is always clean”

For the co-operative movement in Rojava, skill-sharing and knowledge building are core elements to the continuation of their work and values. In a recent report on co-operatives and revolution in Rojava, a member from the House of Co-operatives was quoted as saying:

“You have to renew yourself continuously. Water that flows continuously is always clean. Water that stays in the same place and doesn’t renew itself begins to rot and becomes polluted. How do we renew ourselves? Through practice and education.”

Natalia stresses the importance of education as the co-operative movement gains momentum: “people need to learn how to work in different ways and to learn how to conceive economy in different ways.” “People are so used to essentially being told what to do” Jo adds, “especially when it comes to things like managing land.”

“Building a new world in the shell of the old”

“Being able to develop in any way which is not capitalist is hard” Jo remarks, “especially when all the geopolitical forces are against you.”

But the grassroots co-operative movement is making change here and now. By prioritising people over profit in food production, they ensure that food is accessible and affordable for everyone. By rooting food economies in local communes, they reduce the need for imports, building resilience from within. By rooting co-operatives in the principles of ecology and women’s liberation, and using them as foundations upon which to build diverse communities, they are creating a food system which serves both people and the environment.

“Agricultural co-operatives present an exciting alternative – and as the IWW say, it’s really about ‘building a new world in the shell of the old’.” says Natalia, “we are trying to build food systems that are for everyone – one which cannot be built through capitalism.”

For more information on co-operatives in Rojava, head over to the Cooperation in Mesopotamia website.

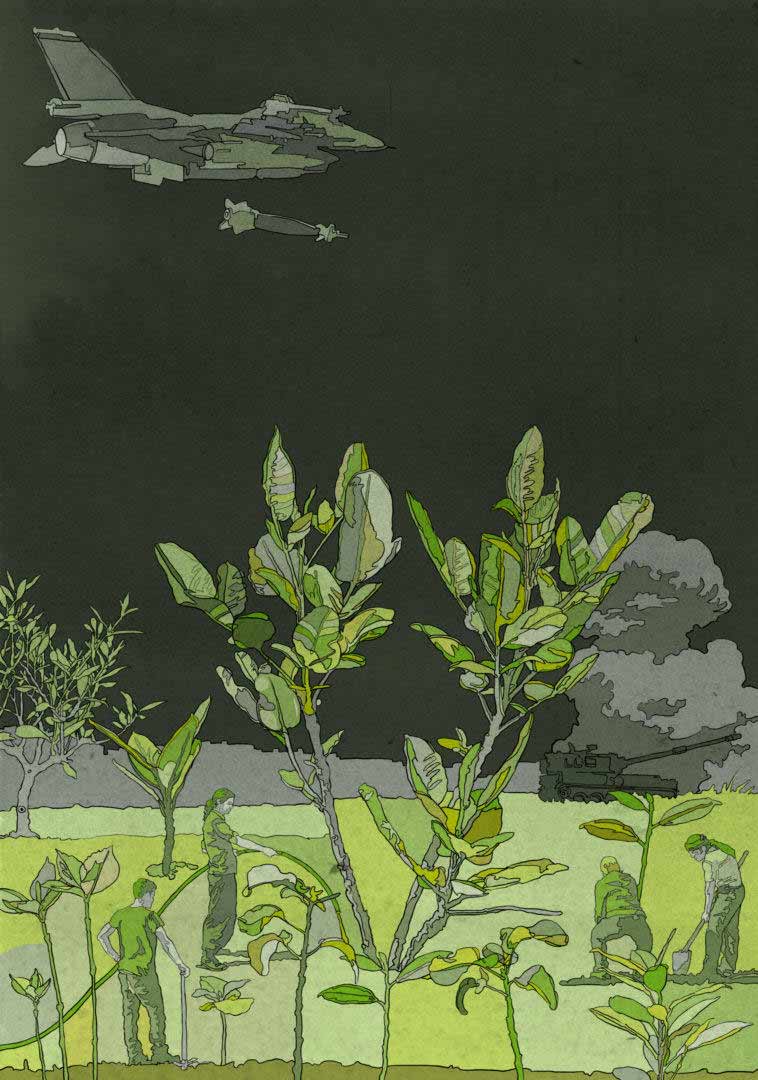

Image credits: Jinwar Women’s Village

Make Rojava Green Again