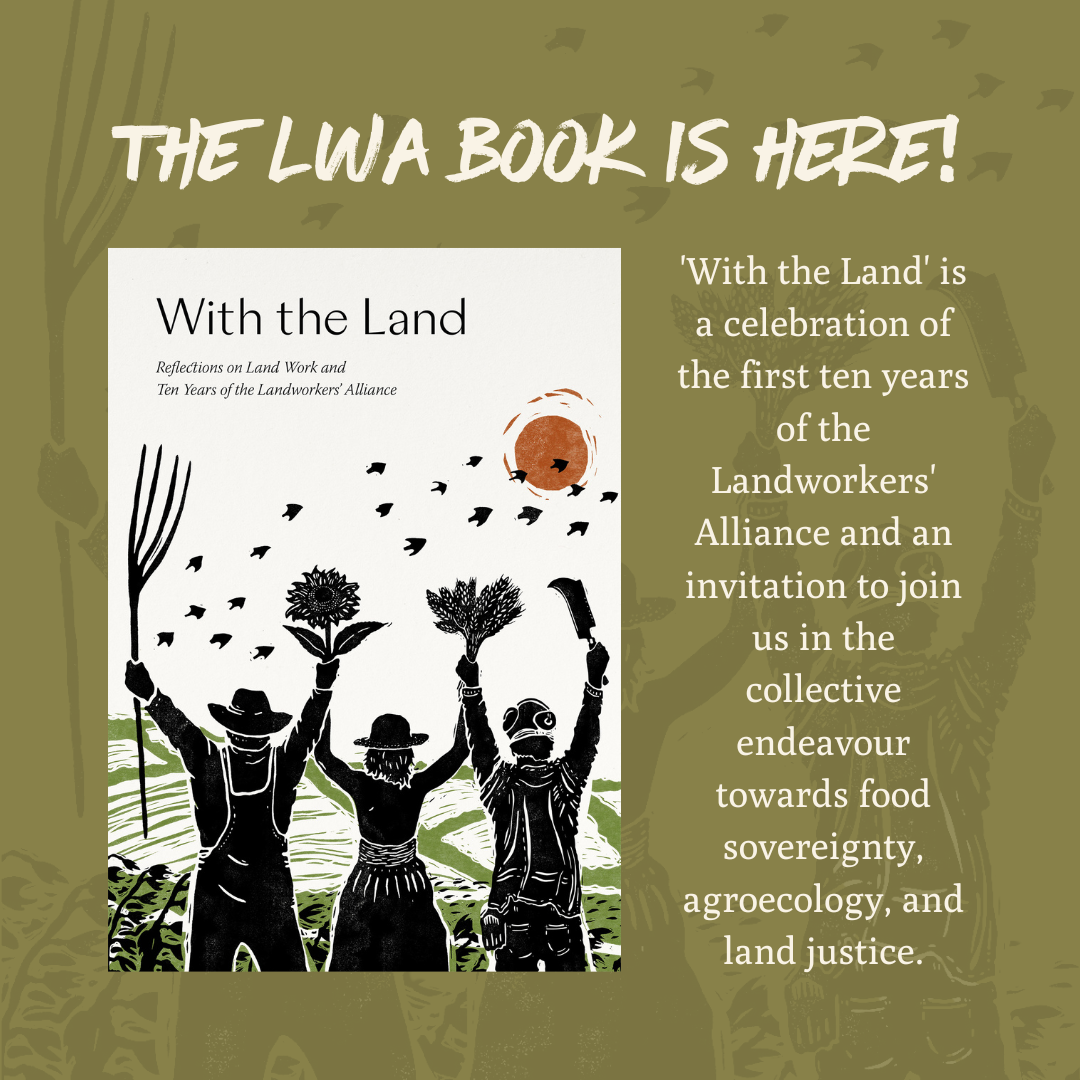

Artist and grower Ione Maria Rojas shares how her relationship with Amaranth has shaped her life, in this extract from our new book “With the Land | Reflections on Landwork and Ten Years of the Landworkers’ Alliance“

How do you go about finding that thing, the nature of which is totally unknown to you?

– Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

For me, it began with amaranth. A towering explosion of magenta and gold, I first met amaranth when it was just a bag of seeds and I was beginning my training in Sustainable Horticulture at Schumacher College. Having been asked to sow the seeds in the circular Hazelip garden, three of us broadcast it over two small beds on the first sunny days of May and waited like nervous parents for it to sprout and grow. Eventually, small neat leaves emerged out of copper stems, a tie-dye effect across the bed as they unfurled in greens, pinks, purples and ambers. I was instantly enamoured.

Our plants grew quickly, and thickly, and strong. They grew steadily upwards, as straight as corn or wheat, but with a bolder, louder palette. I watched with glee as in late August they started to flower, long grainlike buds, hot spiky fingers, tentacled sea creatures of seed and rust. A shock of colour in a Devonshire garden. The colour of brightly painted houses in a loud chaotic city, of tissue paper piñatas suspended over market stalls, of alebrijes and bougainvillea and the sunset after a mountain storm. Watching the amaranth grow transported me to somewhere familiar and forgotten. Fragments of childhood, a family across an ocean, a sleeping dragon lazily blinked one eye open.

“amaranth would be the catalyst for me returning to Mexico and reconnecting with my family there, or that this would be the beginning of a back-and-forth between these wildly different cultures that pulse through my veins.”

I remember when I first read of amaranth’s importance as a food staple of the Mexica, I remember the tiny ‘of course’ feeling in my belly. Known as huauhtli (the name amaranth arrived with Spanish colonisation) the leaves were eaten as greens, the seeds eaten whole or ground into flour for tortillas and tamales, using the same methods that are used by many Mexicans today.

In those early google binges, I found the Spanish codices and Nahua illustrations depicting the huauhtli seed tributes paid to the Mexica capital Tenochtitlan by its provinces. A seed tax. I read descriptions of the offerings made for ceremonies, figurines of the gods made from a huauhtli seed and honey dough that could be broken, shared out and eaten as a collective ritual. My heart raced as I read how the cultivation and use of huauhtli was prohibited by the Spanish, so threatened were they by the indigenous reverence of this plant. Fields of the crop were razed to the ground as a cosmovision rooted in the earth was replaced with enforced Catholicism. I couldn’t quite believe that this same plant, or rather its great-great-great-grandchildren, was now growing outside in our South England soil, revealing itself to us day by day.

The name amaranth, amaranto in Spanish, comes from the Greek amarantos (Αμάρανθος), meaning unfading, everlasting flower. It feels ever more poignant then that it is thanks to the unfading, everlasting love and work of indigenous communities in Mexico that the seed survives today.

What all my internet research back then couldn’t tell me was that amaranth would be the catalyst for me returning to Mexico and reconnecting with my family there, or that this would be the beginning of a back-and-forth between these wildly different cultures that pulse through my veins. It couldn’t tell me that five years later I would sit hunched over a keyboard in a small cafe in Oaxaca, where fields of amaranth grow proudly beyond the city, trying to put into words what has been, and continues to be, one of the most significant relationships in my life.

Ione Maria Rojas is an artist, food grower and somewhat of a migratory bird. Currently based in Devon, she loves how plants can be portals, connecting us to people and places across the world. You can find her website here and follow her on Instagram, here.

This was an extract from the Landworkers’ Alliance 10th Anniversary book, ‘With the Land – Reflections on Landwork and Ten Years of the Landworkers’ Alliance‘, published with the permission of the author, Ione Maria Rojas.